Danube 💙💛❤

🇷🇴 Civilization 🇷🇴

There are certain regions in Europe where the visual manifestation of human symbolic activity in prehistory is livelier than in other areas. Southeastern Europe is one such region with an exceptionally rich heritage of cultural symbolism. A broad variety of visual motifs are found on rock paintings and engravings, on the ornamental designs of pottery, utensils, and architectural forms, and in the use of signs with notational functions, single or in groups, incised or painted on artifacts (Kozlowski 1992: 72 ff.).

The richness of signs in Neolithic and Chalcolithic Southeastern Europe shows considerable variation in space and time. Core symbols that may reflect a large coinage of basic ideas—such as the spiral, the meander, the V sign and others—are wide-spread throughout this culturally interconnected zone, while other symbols have a more limited range and are found only in certain regions. A closer inspection of ornamented and inscribed artifacts reveals that motifs in common use interact with symbols of local range, forming specific regional networks.

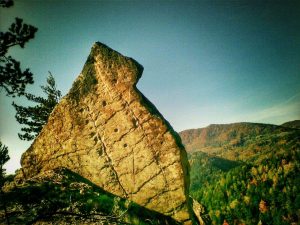

Local traditions of cultural symbolism may have been as diversified as the types of artifacts that are known from the archaeological record. The signs and symbols of Southeastern Europe did not make a sudden appearance. They show striking resemblances with motifs of periods that preceded the Neolithic Era. The cultural roots of symbolism in regional Neolithic societies are associated with the Mesolithic of the seventh millennium BCE in the Danube valley (Lepenski Vir, etc.), and they reach back even deeper in time, showing similarities with the abstract ornamentations of artifacts from the Late Palaeolithic, such as the site of Mezin in Ukraine (c. 15,000 BP). The rise of early agrarian communities in the valley of the Danube and its hinterland produced innovative technologies. In the course of this process, sign use consolidated and assumed the character of an organized form of notation. This transition to writing marks the first experiment of its kind in world history.

The experiment with writing technology in Southeastern Europe produced an original writing system which is addressed here as the “Danube script,” and the cultural horizon in which it originated is referred to as the “Danube civilization.” These terms are synonyms with the earlier terminology, “Old European script” and “Old Europe,” coined by Marija Gimbutas (1991). In a wider perspective, the terminology focusing on the key name “Danube” is likely to facilitate interdisciplinary discussions about the history of writing and about issues relating to ancient writing systems, in particular.

There is a general consensus among scholars that the emergence of early scripts is associated with cultural evolution in the valleys of big rivers or in adjacent areas. This is true for civilizations in Mesopotamia, Egypt, in the Indus valley, in China as well as in Southeastern Europe. Once issues of early writing in the Danube civilization are introduced into interdisciplinary discussions by making terminological reference to the river itself, scholars from other disciplines (Mesopotamian studies, Egyptology, etc.) may readily recognize a congruence with the pattern studied in their own field. In the long run, this may serve as an incentive to promote interdisciplinary cooperation and comparative research on pertinent issues concerning the origins of writing.

Marco Merlini, Italian archaeologist about the Tărtăria tablets and the bones found along with them: ” … the bones, as well as the tablets are very old. It is a certainty. It is our turn to think that writing began in Europe, 2.000 years before the Sumerian writing. In Romania we have a great treasure, but it does not belong only to Romania, but to the whole of Europe.”

Progress in science

Writing research: Orphanage of a

non-established discipline of science…

For more than a hundred years, objects which bear symbols and signs have attracted the attention of scholars, and numerous studies have been published. Unfortunately, dilettants and nationalists have also participated in the discussion about sign use and are in part to blame for the reservations and skepticism that are noticeable in certain academic circles, relating both to the issue of Neolithic symbolism as a field of study and to the findings of writing research. Writing in Neolithic Europe? That sounds unreal to students of ancient writing systems. And why does this idea seem so strange? The answer to this question has much to do with the state of the art of writing research, and this state reflects traditional views about the emergence of writing and about its nature as an institution of early civilization. Throughout its scholarly history, research on the history of writing has been treated like an orphan by the established disciplines of the humanities that deal with language and culture issues.

Strange as it may seem, the history of writing is still an orphan, and is not established anywhere as an independent domain of the cultural sciences, unlike historical linguistics, the cherished child of romantic historicism of the late eighteenth century (Seuren 1998: 51 ff.). It seems like a paradox that the speedy progress made by historical linguistics in the course of the nineteenth century would not enhance the development of writing research in a similar way. In the early phase of historical-comparative studies, before methods of internal linguistic reconstruction had been elaborated, historical linguists had to rely on written records of the languages which were compared for most of their historical evidence. Research on the history of writing has remained, to this day, an arena where experts from different fields and amateurs alike demonstrate their expertise (or speculations) by making pronouncements about the emergence of ancient scripts and their historical development:

– Linguists who are familiar with languages of antiquity and who study the scripts in which they are written may have an understanding of the organization of sign systems and how signs are applied to the sounds of a language, but they may also lack a grasp on archaeological insights about the cultural embedding of ancient societies and their motivation to introduce writing. Linguists sit in libraries and work with written documents but they do not necessarily engage in archaeological studies, investigate assemblages of artifacts (including inscribed objects) in museums or visit excavation sites.

– Archaeologists talk about writing systems without even discussing basic definitional approaches to writing technology. They often observe patterns of consensus and adhere to truisms such as, “We all know what writing is,” or the like. If conventionally generalized viewpoints are given priority, then one cannot expect new questions to be asked and unknown horizons to be explored. Archaeologists do not engage in the study of sign systems (language and non-language related) in a network of communication because that scientific terrain extends beyond the archaeological enterprise into the domain of semiotics.

Archaeologists have made pronouncements about how writing came about in ancient societies without proper methodological tools at their disposal. As for the archaeological record of inscribed artifacts in Neolithic Europe, archaeologists have persistently degraded writing technology as “potters ́ marks” despite the presence of features which clearly speak against such an identification. – Anthropologists amply elaborate on ancient scripts and literacy, but only as safe players, focusing on the established canon of writing systems and leaving out controversial cases. As a rule, scholars of this discipline lack any intimate knowledge of ancient languages and of how various principles of writing apply to differing linguistic structures. Given such limitations, anthropologists miss their chance to refine the methodological instrumentariumabout semiotic markers of writing and the organizational principles of scripts. The approaches used by anthropologists to analyze ancient scripts tend to lack insights into the semiotic infrastructure of sign systems. Knowledge of this infrastructure is indispensable for an understanding of how early experiments with writing were initiated and how writing skills unfolded.

Progress in science, and in writing research in particular, cannot be expected if one adheres to the description of what is already known and accepted by the scholarly establishment. Consensus is not the key to revolutionary breakthroughs in the world of science. Progress arises from the exploration of new horizons which calls for discussions about controversies, instead of remaining silent about unresolved agenda.

Tărtăria Tablets

In “The Danube Script and Other Ancient Writing Systems: A Typology of Distinctive Features,” linguist Harald Haarmann discusses the early experiment with writing in Southeastern Europe and provides an introduction to sign systems, notational systems and the status of writing in the realm of culture. He also discusses the principles of writing common to ancient scripts and outlines a typology of writing systems, principles and techniques of writing, and parameters for comparing ancient writing systems.

Italian researcher Marco Merlini discusses the historical background and significance of three engraved tablets and related artifacts discovered in 1961 near the Romanian settlement of Tărtăria. The “Tărtăria tablets” have occupied a unique and controversial position in debates about the earliest European writing. His paper, “Challenging Some Myths About the Tărtăria Tablets: Icons of the Danube Script,” presents the results recent investigations on the context and datingof this discovery and the possible significance of the tablets as icons of the Danube script.

Mathematical algorithms were developed to correlate data in order to discern direct or indirect connections between objects and their characteristics within specific archaeological contexts. Correlated and seriated tables are used to discern the evolution of different categories of signs and symbols. In the uthor’s view, information obtained from these tables indicates the existence of a “sacral writing” with a dynamic evolution which developed in the Late Neolithic Vinča C culture groups, such as Turdaş, Gradešnica and others related to Vinča C.

The pioneering research by American archaeologist/linguist Shan M. M. Winn on early script signs in the central Balkans is introduced here in three parts. His paper, “The Danube (Old European) Script: Ritual use of Signs in the Balkan-Danube Region c. 5200-3500 BC,” recounts his initial study of symbols on Vin…a and Tisza artifacts in northern Yugoslavia and southern Hungary. After collecting signs from more than forty Vinča sites in 1971, he catalogued 210 sign types in his doctoral dissertation, Pre-Writing in Southeastern Europe (1973). He chose the term “pre-writing” as a result of scholarly resistance to his original use of the term “script.” The second part describes his reassessment of the signs, including fifteen categories and 242 signs and symbols based on distinctions in usage. The final part focuses on two spindle whorls that he discusses as evidence for writing. Based on the premise that the inscriptions are best interpreted in the context of ritual, Winn identifies several signs and submits a tentative interpretation.

Concluding thoughts

It is significant to recognize that the earliest farmers of Southeastern Europe developed mature, sustainable societies that required the intentional transmission of accumulated knowledge. It is quite possible that the long-term cultural potency of these societies was enhanced by the ability to concentrate collective memory and communal concepts beyond the limitations of oral tradition. People found ways to record essential ideas onto media more durable than individual human minds. While several authors in this issue have offered suggestions about the possible significance of certain signs and symbols, we would like to emphasize that it is not necessary to decipher the meanings of inscriptions in order to prove the existence of a system of visual communication.

However, the ubiquity of inscribed objects within domestic contexts, used for ritual as well as practical purposes, speaks for the widespread use of signs and symbols—not for economic bookkeeping, as in Mesopotamia—but as an intrinsic expression of cultural embedding within the local landscape of regional communities and throughout the larger parameters of the Danube Civilization.

Harald Haarmann: “The world’s earliest known form of writing is the one from Tărtăria – Romania. The Danubian civilization is the first great civilization in history, thousands of years older even the Sumerian one.”

360 °

Source: the Danube Script

@ Harald Haarmann & Joan Marler

© Institute of Archaeomythology 2008

See more 🇷🇴 The Danube Valley 🇷🇴

| 🇷🇴 reBranding ROMANIA 🇷🇴 CSR project by B2B Strategy ™ |

Comments are closed.