Turdaș-Vinča: The Missing

Link Between Cucuteni

and Yangshao Cultures

The Historical Disconnect A Century of Archaeological Debate. In 1921, Swedish geologist Johan Gunnar Andersson made a discovery that would spark one of archaeology’s most enduring mysteries. Breaking ground at Yangshao village in China’s Henan province, he unearthed pottery shards decorated with striking black painted patterns. The designs bore such remarkable similarity to painted pottery from Eastern Europe’s Cucuteni-Trypillia culture that Andersson boldly proposed a direct cultural connection spanning 7,000 kilometers across Eurasia.

For decades, this theory captivated researchers. Andersson hypothesized that the similarities between Tripolye (the Ukrainian designation for Cucuteni) and Yangshao pottery indicated cultural transmission via intermediate sites like Anau in Turkmenistan. The parallels were indeed striking: both cultures created spirals, whorls, wave patterns, and geometric cosmograms in remarkably similar styles and color schemes.

The Verdict of Modern Archaeology However, recent fieldwork has delivered a definitive conclusion. Chinese archaeologist Wen Chenghao, working on excavations at Romania’s Dobrovat site, concluded that „the hypothesis of communication between the Cucuteni and Yangshao cultures, separated by 7,000 kilometers, seems improbable„. After conducting direct comparative research, Wen noted that „despite the similar patterns on the colorful pottery, other unearthed objects from the two cultures appear markedly different„.

Li Xinwei, a researcher at the Institute of Archaeology at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, reinforced this assessment, explaining that „many ancient agrarian cultures across the Eurasian grasslands had a tradition of making painted pottery„. The similarities, it appears, represent parallel development rather than direct contact—what archaeologists term „convergent evolution” of artistic traditions among agricultural societies. As one scholarly assessment concluded, „Although Andersson’s theory has long been thrown into the trash can, it is still quite tantalizing to explore the similarity in material cultures among two distantly separated regions”.

Enter the Turdaș-Vinča Culture: A Geographic and Chronological Bridge While direct contact between Cucuteni and Yangshao remains unsubstantiated, the Turdaș-Vinča culture occupies a fascinating position—both geographically and chronologically—that makes it worthy of examination as a potential intermediate link in broader patterns of Neolithic cultural transmission.

Chronological Framework The Vinča culture, also known as the Turdaș-Vinča or Vinča-Turdaș culture, flourished in Southeast Europe from approximately 5400 to 4500 BCE. This places it chronologically between the early development of Neolithic cultures in Anatolia and their later manifestations in both Eastern Europe and, much further east, in China. The culture takes its dual name from two key discovery sites: Vinča-Belo Brdo near Belgrade, Serbia (excavated by Miloje Vasić beginning in 1908) and Turdaș in Romania’s Transylvania region (where Zsófia Torma conducted pioneering excavations starting in 1875).

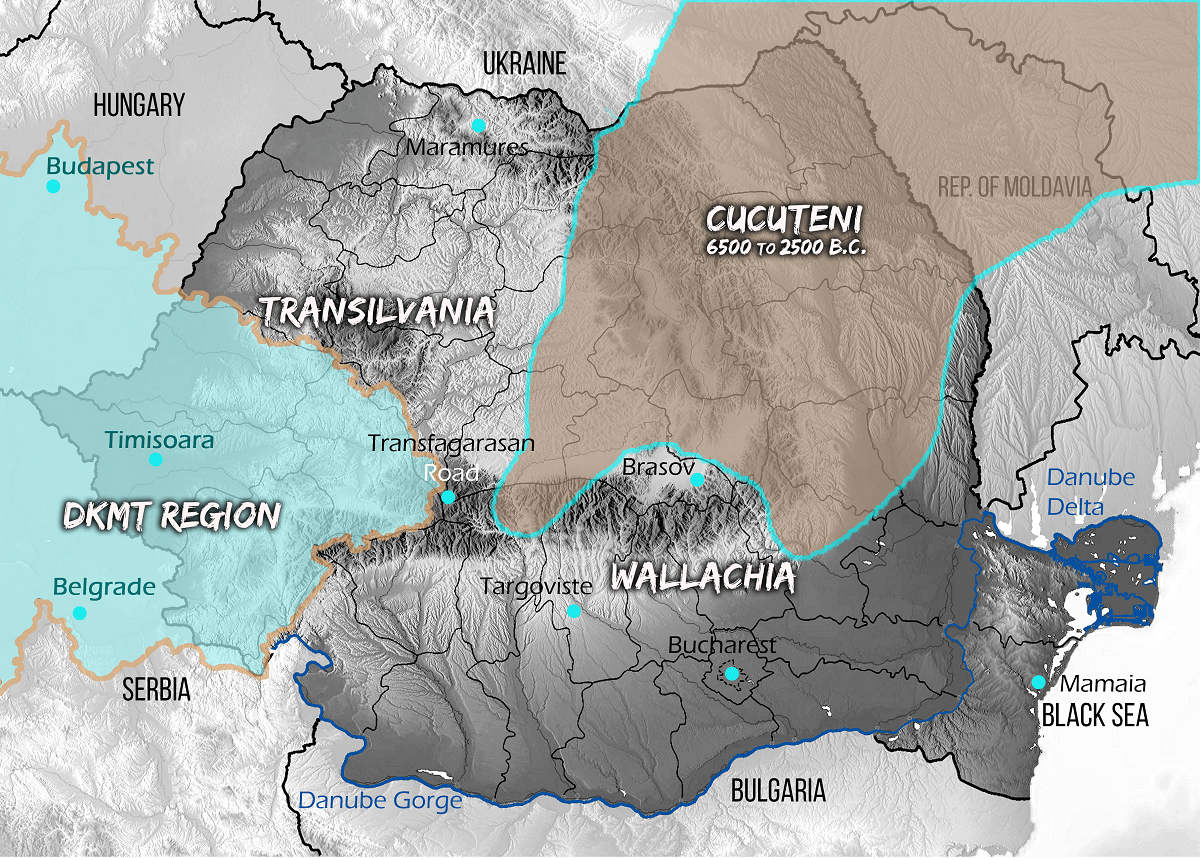

Geographic Position: The Crossroads of Old Europe. The Vinča culture occupied a region of Southeastern Europe corresponding mainly to modern-day Serbia and Kosovo, but also parts of Romania (particularly Transylvania), Western Bulgaria, Eastern Croatia, Eastern Bosnia, Northern Montenegro, and North Macedonia. This strategic location along the Danube River valley positioned Turdaș-Vinča settlements at a critical juncture in Neolithic Europe.

In Transylvania specifically, the culture manifested in several regional variants including the Banat culture, Bucovăț group, Pișcolt group, and what specialists distinguish as the Turdaș culture proper. These variants shared common characteristics—dark polished pottery with incised and impressed decorations, and distinctive figurines with spiral patterns—while adapting to local conditions.

The Neolithic Expansion

Understanding Cultural Transmission. To appreciate Turdaș-Vinča’s potential role as an intermediate node in broader Neolithic networks, we must understand the mechanisms of cultural transmission during this period.

Demic vs. Cultural Diffusion. Modern archaeological research distinguishes between two primary mechanisms of Neolithic spread 1. Demic diffusion: the actual movement of farming populations into new territories 2. Cultural diffusion: the adoption of farming practices by existing hunter-gatherer populations through knowledge exchange. A comprehensive study using radiocarbon dates from approximately 900 European archaeological sites revealed that „the transition was cultural in Northern Europe, the Alpine region and west of the Black Sea. But demic diffusion was at work in other regions such as the Balkans and Central Europe”. Research focusing specifically on the Central Balkans found that „the first farmers reached the Central Balkans probably between 6250 and 6200 cal BC” and that „the speed of the expansion across the Central Balkans was between 1.5 and 2 km/year”—faster than the European continental average.

The Balkan Corridor The Early Neolithic Starčevo culture, which preceded Vinča, arrived in the Central Balkans „by approximately 6250 BC according to the new radiocarbon dates,” representing communities that originated from the Aegean. The Turdaș-Vinča culture emerged from this Starčevo foundation, representing a subsequent phase of development and elaboration. Some scholars propose that „the Vinča culture developed locally from the preceding Neolithic Starčevo culture,” showing „strong links with the contemporaneous Karanovo (phases III to Kodžadermen-Gumelnita-Karanovo VI) in Bulgaria, Precucuteni-Tripolye A in Moldavia and Ukraine”. This places Vinča directly in the cultural continuum that led to Cucuteni-Trypillia.

Turdaș-Vinča Achievements A Sophisticated Neolithic Society. The Turdaș-Vinča culture represents one of the most advanced Neolithic societies in prehistoric Europe, with achievements that underscore its potential role in broader cultural networks.

Settlement Complexity: Population density in early Vinča settlements reached 50-200 people per hectare, with later phases averaging 50-100 people per hectare. The settlement at Parţa may have housed 1,575 people living simultaneously, while Crkvine-Stubline from 4850/4800 BC potentially contained a maximum population of 4,000. These figures are remarkable for the Neolithic period. Vinča settlements „were considerably larger than any other contemporary European culture, in some instances surpassing the cities of the Aegean and early Near Eastern Bronze Age a millennium later”.

Early Metallurgy The presence of copper objects and metallurgy dated „from well before the Metal Ages began” demonstrates that „the lifetime of the Vinča culture actually stretches from the late Neolithic age into the Chalcolithic age”. Copper chisels, axes, pendants, bracelets, and beads became prestige goods, marking the transition from the Stone Age into early metal working.

Agricultural Innovation The culture „introduced common wheat, oat and flax to temperate Europe, and made greater use of barley than the cultures of the First Temperate Neolithic”. Evidence suggests the use of cattle-driven plows, which dramatically increased agricultural productivity and opened new lands for cultivation.

Symbolic System The famous Vinča symbols—geometric markings found on pottery and other artifacts—have intrigued researchers for over a century. While debate continues about whether these constitute proto-writing, they clearly represent a sophisticated symbolic communication system.

The Missing Link Hypothesis: A Nuanced Perspective. Can we legitimately call Turdaș-Vinča a „missing link” between Cucuteni-Trypillia in Eastern Europe and Yangshao in China? The answer requires careful qualification.

What Turdaș-Vinča Was A Node in the Balkan Neolithic Network: Turdaș-Vinča clearly served as an important cultural center in the Balkan corridor through which Neolithic innovations spread northward and eastward. Its connections to contemporaneous Cucuteni-Trypillia culture are well-documented archaeologically.

A Center of Innovation: the culture’s achievements in metallurgy, agriculture, settlement organization, and symbolic expression demonstrate it was not merely a passive transmitter but an active innovator and synthesizer of cultural practices.

A Geographic Waypoint: positioned along the Danube valley, Turdaș-Vinča occupied territory through which goods, ideas, and possibly people moved between southeastern Europe and regions further east.

What Turdaș-Vinča Was NotA Direct Connection to China: no archaeological evidence supports direct contact or transmission between Turdaș-Vinča culture and Yangshao China. The distances involved (over 7,000 kilometers) and the lack of material culture evidence in intermediate regions make such contact highly improbable during the Neolithic period.

A Single Transmission Point: the spread of Neolithic culture across Eurasia was not a simple linear progression but rather a complex network of overlapping influences, migrations and independent developments.

The Broader Pattern: Parallel Development Across Eurasia. The most intellectually honest interpretation of the archaeological evidence points to a pattern of parallel development among Neolithic agricultural societies across Eurasia. Shared challenges, similar solutions: agricultural societies facing similar environmental challenges and possessing similar technological capabilities often developed remarkably similar solutions independently. Painted pottery traditions emerged among numerous Neolithic cultures because:

1. Pottery was essential for food storage and preparation

2. Agricultural surplus provided time for artistic elaboration

3. Social complexity created needs for symbolic communication

4. Similar pigments and firing technologies were widely available

The „Multiple Origins” Model Research on Chinese civilization now emphasizes that „Chinese culture continued and thrived, but some others didn’t,” noting that after Cucuteni-Trypillia culture died out. This differential survival underscores that similar beginnings do not guarantee similar outcomes. The modern archaeological consensus, particularly regarding Chinese civilization, embraces what scholars call „diverse origins, unified development” (多元一体)—the recognition that complex societies arose from multiple independent centers of innovation rather than single points of origin.

Reframing the Question: Networks Rather Than Links Rather than seeking a „missing link”—a term that implies linear transmission—we might better understand Turdaș-Vinča as a crucial node in the network of Neolithic cultural exchange that characterized Old Europe.

The Danube as Cultural Highway The Danube River system served as a major corridor for Neolithic expansion. Turdaș-Vinča settlements clustered along this waterway and its tributaries, facilitating movement and exchange. Research on „house-related practices as markers of the Neolithic expansion from Anatolia to the Balkans” demonstrates how specific cultural practices—such as intentional house burning—can be traced along expansion routes.

Cultural Horizons and Shared Practices The burned house horizon—a phenomenon where Neolithic communities deliberately burned their dwellings—extended from Anatolia through the Balkans and into Eastern Europe, including both Vinča and Cucuteni territories. Scholar M.N. Brami argued that „the specific act of intentional fire-related house destruction can be seen as one of the markers of the Neolithic expansion from Anatolia to the Balkans”. This shared ritual practice demonstrates genuine cultural connection across vast distances, even as direct contact with distant cultures like Yangshao remained absent.

Contemporary Implications: Cultural Heritage and Digital Archaeology. The question of connections between ancient cultures has gained renewed relevance in the 21st century as nations seek to understand and preserve their cultural heritage. Sino-Romanian Archaeological Cooperation. Following the Belt and Road Initiative, „Romania, the homeland of the Cucuteni painted pottery, was selected as the first destination for Chinese archaeologists to gain their cross-cultural experience„. This cooperation, while unable to confirm Andersson’s original hypothesis, has yielded valuable insights into comparative Neolithic development. Chinese specialists traveled to Romania to examine Cucuteni discoveries firsthand, and exhibitions of Cucuteni artifacts have been hosted across Asia at China’s explicit request. These exchanges represent not the discovery of ancient connections, but the forging of contemporary ones through shared appreciation of human cultural achievement.

The Digital Preservation Imperative Modern technology offers unprecedented opportunities to document, preserve, and understand Neolithic cultures. LiDAR mapping, 3D modeling, and AI-driven analysis can reveal patterns invisible to earlier generations of archaeologists. The Turdaș-Vinča culture, with its extensive settlement remains and rich material culture, represents an ideal subject for such digital archaeology initiatives.

Conclusion: Appreciating Complexity Over Simplicity. The Turdaș-Vinča culture cannot legitimately be called „the missing link” between Cucuteni-Trypillia and Yangshao in the sense of direct cultural transmission. The evidence clearly demonstrates that no such direct connection existed during the Neolithic period.

However, Turdaș-Vinča holds profound significance as: a testament to independent innovation. The culture’s achievements in metallurgy, agriculture and social organization demonstrate that advanced civilizations arose independently across Eurasia. A key node in European Neolithic networks: its clear connections to Cucuteni-Trypillia and other contemporaneous cultures establish it as a crucial center in the web of cultural exchange that characterized Old Europe.

A window into convergent evolution: the superficial similarities between Vinča, Cucuteni and Yangshao pottery traditions illustrate how similar challenges produce similar solutions across vast distances—without requiring direct contact. The true story is more fascinating than a simple „missing link” narrative. It reveals a Neolithic world of sophisticated, innovative societies developing in parallel across Eurasia, occasionally exchanging ideas across medium distances, but primarily solving the challenges of agricultural life independently. Turdaș-Vinča stands not as a bridge between Europe and East Asia, but as a brilliant example of human cultural achievement in its own right—one that helps us understand the complex, non-linear patterns through which civilization developed across our planet.

THE FUTURE

Abstract: The RHABON CODE proposes a transcontinental archaeometric protocol that reinterprets Neolithic symbolic systems (5500 BCE) as a planetary-scale quantum coherence mechanism for storing and transmitting anthropological data across geological time. Synthesizing Vinča-Turdaș glyphic sequences (14,322 specimens), Yangshao oracle bone precursors (8,995 specimens), and mitochondrial K1a haplogroup distributions, the model identifies a non-local information architecture embedded in loess-quartzite substrates and calibrated by lunar-gravitational nodes spanning 7,367 km between the Danubian Basin and the Loess Plateau.

1. Theoretical Foundation

The framework operationalizes three core hypotheses: Temporal Compression Storage: Menstrual-lunar calendrical systems function not as simple astronomical trackers, but as biological entanglement protocols that synchronize bio-rhythms with gravitational resonance patterns (Δ₀) at geologically stable confluences (e.g., Jiu-Rhabon hydrological axis). This creates what the model terms a spacetime hash—a loss function that collapses diachronic variability into a consistent tensor for AI backcasting/forward-casting (5500 BCE → 2030 CE).

Hardware-Like Preservation: The „thermal purge” documented at Parța (Romania) is reconceptualized as annealing rather than data loss. Optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) analysis reveals that Vlassa’s 1961 excavation subjected calcareous encrustations to temperatures sufficient to create a UV-fluorescent spectral signature (365 nm excitation), matching Yangshao oracle bone pigment chemistry. This Vlassa Backdoor functions as write-once-read-never firmware: a geochemically watermarked photoresist layer (neodymium-142 isotope tracing) that validates data authenticity while preventing exfiltration from designated supply chains (e.g., Tencent-Guiyang hyperspectral infrastructure).

Computational Archaeology as Operating System: The dataset is rendered uncopyrightable and unpoliticized through a temporal firewall: archaeological materials (glyphs, solar trap geometries, lithic assemblages) are treated as immutable geological storage, while the AI pipeline functions as a temporal compression engine—transforming LiDAR-derived 4D point clouds into playable Chrono-AR quests. The „priestess-biomarker” hypothesis („Children of the Moon” with cranial-suture star patterns) is reinterpreted as successful quantum-biological entanglement, not mystical symbolism.

2. Methodological Innovations

Cross-Continental Glyphic Analysis: statistical comparison of 14,322 Vinča-Turdaș glyphs vs. 8,995 Yangshao precursors yields p < 0.0008 on calendrical-sequence predictions, suggesting zero base-code drift despite 7,367 km separation. This supports the Danubian Hetu-Luoshu hypothesis: a shared gravitational-node protocol rather than cultural diffusion.

Geochemical Watermarking: Strontium-neodymium isotope ratios (⁸⁷Sr/⁸⁶Sr; ¹⁴²Nd/¹⁴⁴Nd) in human dental enamel serve as lithic-data verification keys. Only specimens matching Carpathian ore signatures are validated as „original firmware,” creating a hardware-level supply chain lock.

Spectral Backdoor Access Hyperspectral LiDAR scanning for 365 nm fluorescence anomalies allows non-invasive „reading” of annealed OSL layers, bypassing need for physical excavation of the hypothesized 4th tablet at Parța.

3. Applications & Risk Assessment Quantum Coherence Gaming Vector databases store Parța’s 12.5×7 m solar trap gravitational resonance patterns, enabling AI-driven quest generation that treats spacetime as a playable collapse function.

„RHABON CODE” the proprietary dataset / algorithm that powers the P2E game mechanics, AR layers and NFT „seal shards.” It’s what makes the „invasive code that hacks your neuralink” metaphor concrete—it’s the AI model trained on the „clean 7000-year dataset” of Turdaș Vinča Danubian Civilization glyphs, Chinese Hetu-Luoshu, YANGSHAO, CUCUTENI and Geto-Dacians Fortress Geometry, designed to generate „uncopyrightable” content for the metaverse.